From time immemorial and particularly since the mid-20th century, enterprises, institutions (both public and private) and companies have been adopting new forms of organisation aimed at sharing power more effectively, becoming more agile and thus reducing the importance of – or even doing away with – hierarchies. Indeed, in recent years this trend has been accelerating.

Wanting to share power is a noble undertaking, but it also implies accepting greater responsibility. The idea is conveyed nicely in English with the expression “making oneself accountable”. Accepting responsibility in turn implies living with the consequences that derive from it.

In this context, decision-making is one of the key aspects of devolving power.

For this to work, three basic factors need to be taken into account and acted upon:

- Personal autonomy,

- The resources a person can draw on,

- The culture in place

Where the notion of “power” is concerned, please see the article “Leadership: legitimate power” (https://www.lp3leadership.com/site/leadership-legitimate-power).

Power

Despite the negative connotations it has acquired as a result of our reading and perceptions of it, power is in fact a neutral concept. The word derives from the Latin potere (meaning to have the capacity to do something) and is therefore neutral; it is the use to which it is put (the way we use sources of power) that is either positive or negative. For example, I can use money – a classic source of power – to buy weapons or make a donation to a good cause.

As for having to take responsibility, this sometimes takes us out of our comfort zone.

On this topic, please read my article “Employability, comfort zones and conscious breathing” (https://www.lp3leadership.com/site/employability-comfortzones-and-conscious-breathing/ ).

How easy we find it to venture outside our comfort zones and take risks will depend on the resources we have available to us and the issues we have to face.

Courage

My article on the concept of courage: “Management: affirming courage” (https://www.lp3leadership.com/site/management-affirming-courage/ ) will give you some pointers on how to enable your friends, children, employees and colleagues to overcome their fears and so act with greater courage.

Please note that you must never say to a person: “Go on, be braver!”. This is because everything depends on the fears a person has to cope with. As we can never know what fears others are having to contend with, we have no right to tell them to be braver. We can, however, act on the three levers mentioned earlier.

The levers you can use, develop and strengthen are:

- Someone’s personal resources, by valuing and developing the person concerned (training, coaching…)

- The positive experiences you are going to facilitate for them, for example by delegating a task in which they can be successful

- The person’s “naivety”, while covering their back and not blaming them if they make a mistake. This means that even if a person is unaware of all the risks involved in a task or undertaking (which is what I mean by naivety, like that of a child), they will dare to do something, have a go, because they know they can learn from their mistakes and you won’t rap them over the knuckles if they get it wrong. On this subject, please read my article “The right to make an honest mistake”. (https://www.lp3leadership.com/site/the-right-to-commit-errors-but-not-faults/ )

Decision-making

Now let’s consider the key issue, decision-making, as the main factor in devolving power.

This is first and foremost a cultural issue. How often have I come across enterprises that wanted to adopt a more agile approach, wanted to devolve power, and put in place a raft of tools and measures for this purpose, but finally stumbled over the fundamental problem of culture: “Do I have the right to take decisions?” “Are we being real about this or is it just lip service?”.

As I mention in the article “Holacracy & Co.: a question of autonomy, teamwork, cooperation and, above all, leadership” (https://www.lp3leadership.com/site/holacracy-co-a-question-of-autonomy-teamwork-cooperation-and-above-all-leadership/ ), not all enterprises or organisations can put such systems in place.

The fact is that not everyone wants to take decisions and live with the consequences; not everyone has broad enough shoulders to bear the consequences. Decision-making structures therefore need to be clear and suited to an enterprise, to an organisation and its staff, without leaving some people looking on from the sidelines.

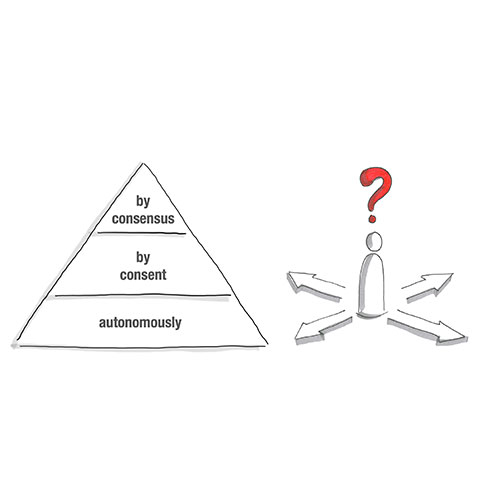

We therefore need to consider three levels or types of decision-making:

- decisions taken by consensus,

- decisions taken by consent,

- decisions taken autonomously.

A decision by consensus requires that all the persons present or involved be in agreement. This takes up a lot of time and resources, and the solutions arrived at tend to be uninspiring, not far removed from the status quo. Decisions of this kind are best avoided.

Decisions by consent are reached mainly in the context of new approaches such as holacracy or sociocracy. This can be a useful procedure, provided it is well managed. What tends to happen is that someone proposes and explains a decisions, a plan or a measure and, if there are no valid objections, the proposal is accepted.

The key thing here is to make very clear what constitutes a valid objection and what the valid objection relates to (vision, mission, principles of conduct, principles of management). It is therefore important to structure and guide the discussion.

So what constitutes a valid objection? An objection is valid if the decision, plan or measure:

- is explicitly contrary to the mission (raison d’être), vision or values of the enterprise. For example, if an enterprise producing micromotors for humanistic purposes decides to supply an armaments factory;

- presents one or more identifiable risks that would harm the reputation of the enterprise, cause it to lose a competitive advantage or delay the marketing of a key product;

- would lead directly to one or more negative consequences. This could be a failure to achieve an objective, excessive costs or the laying off of staff;

- as an adjunct to the previous point, would lead to one or more definite (not merely conjectural) consequences for which there was no remedy. For example, if this decision were adopted, a competitor would be entitled to buy back a production licence, which would have a major adverse effect on the enterprise;

- would directly impact the room for manoeuvre of one of the persons present, the achievement of objectives or the quality of the products and services of one or more or the persons present or concerned;

- would cause one or more of the persons present to be alienated, for example because the proposed measure was contrary to their personal values.

Therefore, if a valid objection is raised, it must be discussed with a view to finding a satisfactory way of reformulating or adapting the proposal, plan, decision or measure. If necessary, the proposal will be rejected or will have to be reworked and presented again at a later date.

Even if all this is appropriately handled and done in the right way, a problem still remains. If a decision taken and approved by consent turns out to be wrong, it is very difficult to make an about-turn and amend the decision, halt the project or cancel the measure. Because the persons present have invested time and resources, it is difficult for them to “own up” to failure.

This is why the third form of decision, a decision taken autonomously, is the most effective and fruitful. It is important that a decision-maker’s room for manoeuvre be clearly defined, and that those concerned have the resources and support they need to take decisions for themselves without having to go through a complex and costly process. For the sake of speed and flexibility, there is no better way.

The fact is that if a person is allowed to take decisions, make mistakes, learn from them and thereby grow in stature, it will be easier for them to realise at an early stage if they are making a mistake, go back on a decision, modify it and so become more agile.

To sum up, let’s allow as many people as possible to take decisions, thus boosting their autonomy and strengthening their resources, while at the same time covering their backs (giving them a sense of security).

If this is to be achieved, a corporate learning culture is required, with a double feedback loop.

In other words, if a person makes a mistake, they analyse and learn from it (1st loop); they then pass on the lesson they have learned to others in the organisation or institution (2nd loop).

When it comes to decision-making, therefore: go for it!